By Javier Caletrío

There is a man sitting across the room in the shadow, but I know who he is. His brilliant eyes burn through shade. He tells me that if I sit still and listen then all the stories of the world will come to me.

— From ‘Lives’ in Brian Daldorph’s Outcasts

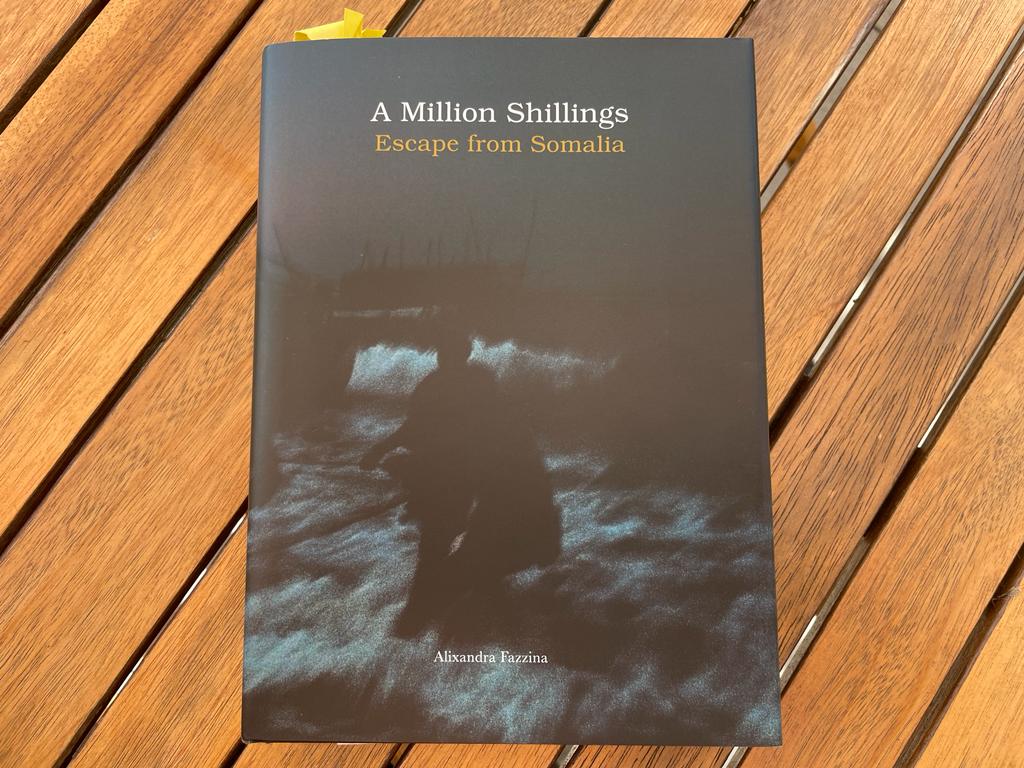

In A Million Shillings men and women sitting across rooms in shadows tell stories about journeys. Theirs are tales of the Horn of Africa seldom recounted in western media or in ‘official’ narratives, academic or otherwise, of displacement as a human tragedy. Perhaps these individual accounts, so often explained in the press as cold statistics, could have been told with words, perhaps with poetry. Instead, photojournalist Alixandra Fazzina has depicted them with images.

Of course there is no shortage of images in Western media to evoke the Horn of Africa, images of war, famine and so called ‘natural disasters’. Fazzina’s photos though avoid the frontline of the dramatic event that momentarily attracts media attention and are instead concerned with the people whose lives and difficult circumstances continue once the cameras leave, who have to cope with the reverberations of those events in their lives, landscapes and memories. In so doing her images go beyond the simplifying crisis narrative to search for the lived and enduring meanings that displacement can have for specific people. This does not mean that the book selectively focuses on pleasant moments for there are no such moments in the journey—at best there are moments when resting may be less troubled. Neither does this mean that war or violence are blocked out. On the contrary, perhaps the power of these images is precisely the way in which what is shown evokes that which remains invisible to the reader.

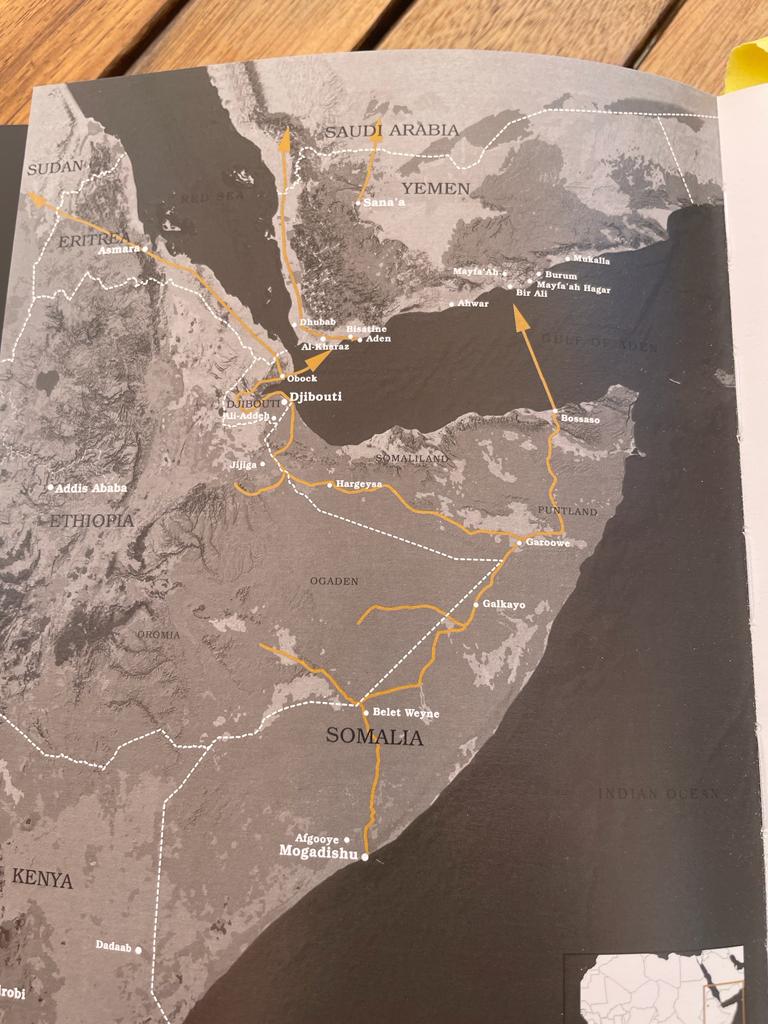

At the time when the migrants and refugees telling their stories were fleeing Somalia in search of a better life in Aden, the Yemeni city named, ironically for the migrants, after the fabled paradisiacal garden. Most of them had begun their journey in the now almost depopulated Mogadishu, but the book starts on the outskirts of the coastal port of Bossaso and one of the world’s biggest hubs for smuggling people, and follows the migrants to the Arabian Peninsula through the Gulf of Aden.

By the time they arrive in Bossaso, most will have been be threatened, robbed and abused on the way. One in twenty will die during the journey, drowned at sea, shot or beaten to death by the smugglers. Those who make it will see their hopes and expectations evaporate rapidly. Disillusioned in Yemen where they are automatically granted refugee status but are barred from formal employment and are therefore confined to a life in relative peace but with no prospects, many will try to continue their journey to Saudi Arabia risking deportation back to Mogadishu. Others will attempt a land route towards Europe. Only a small minority of those who arrive to Yemen will qualify for resettlement as refugees in a third country.

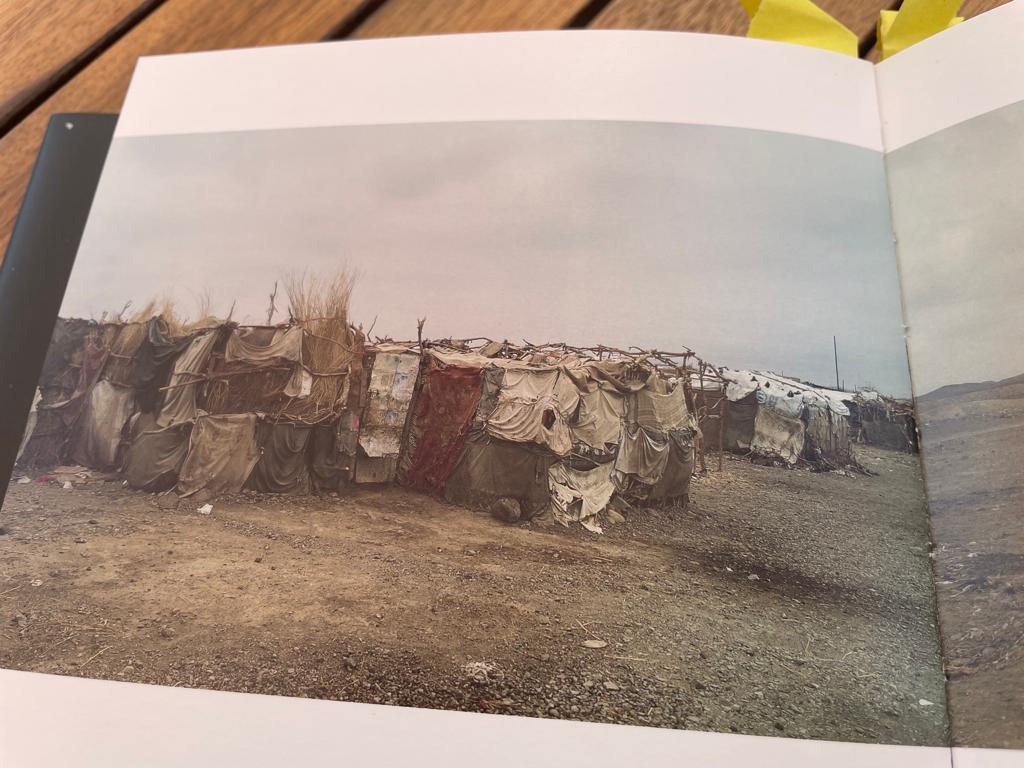

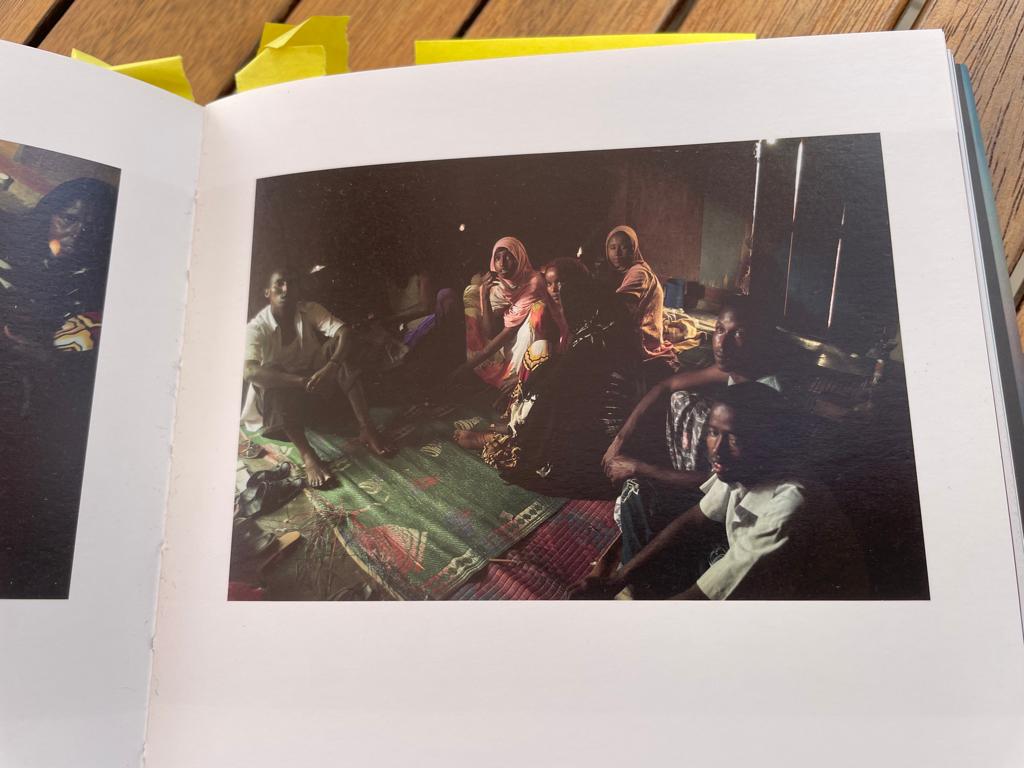

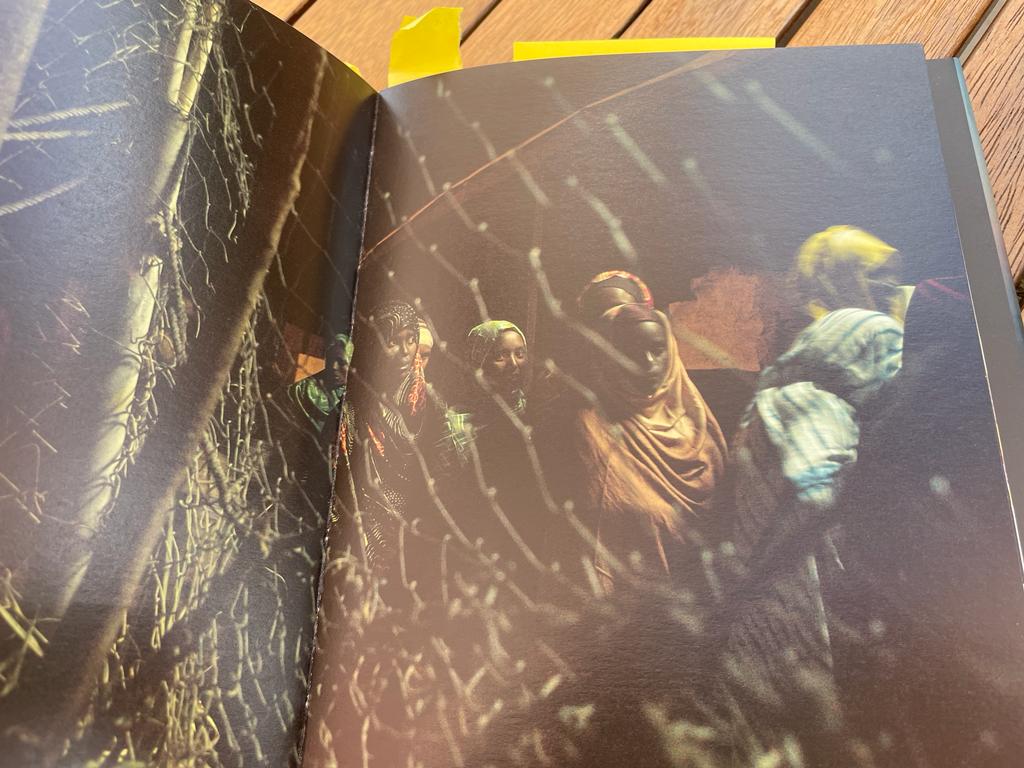

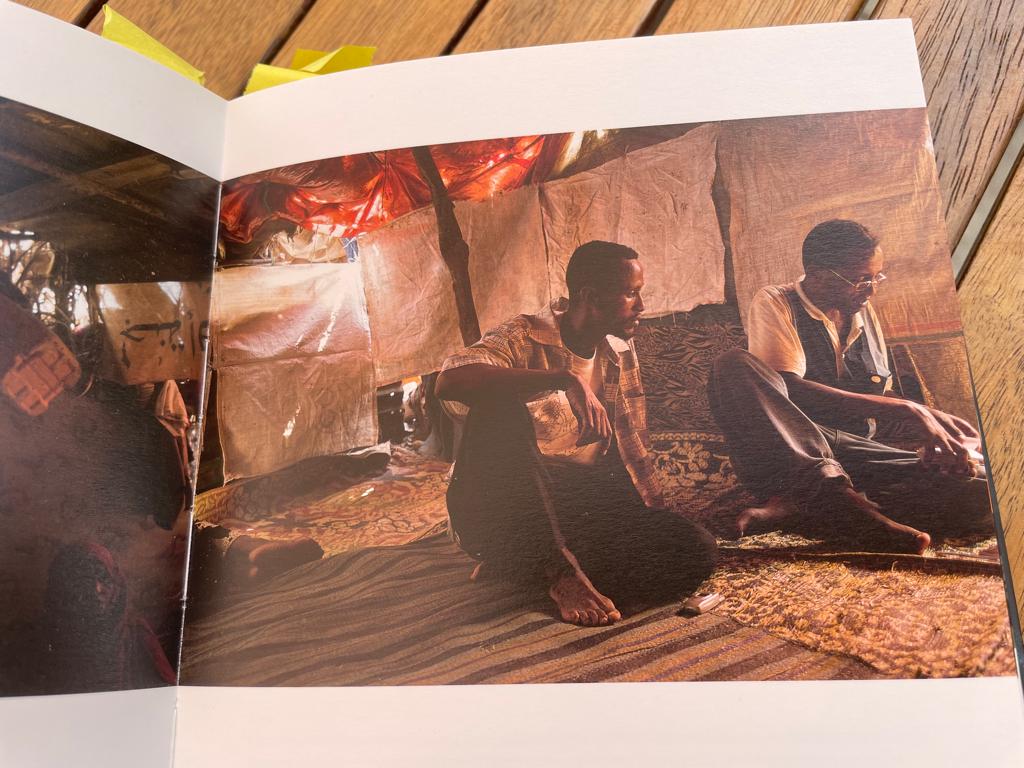

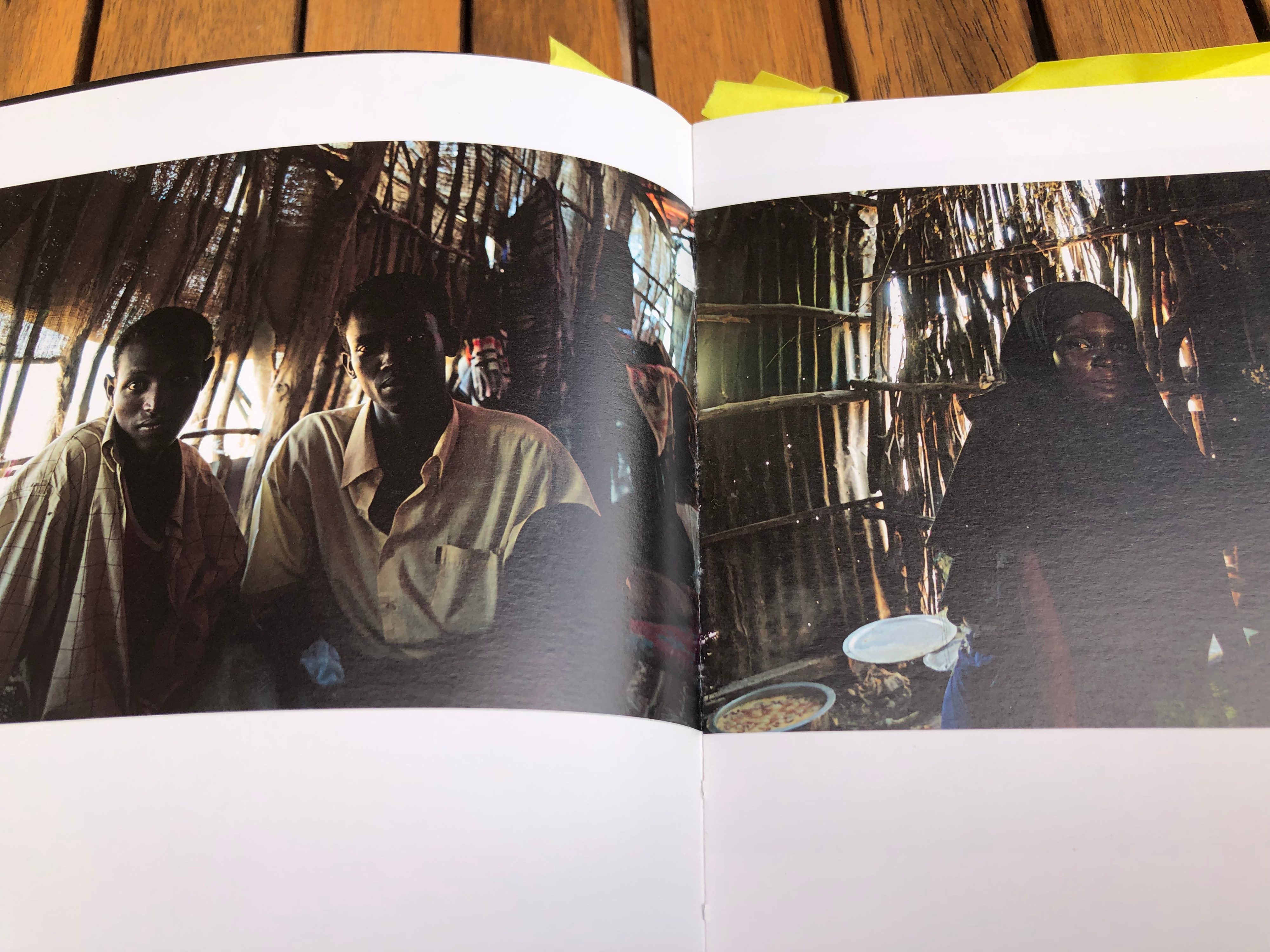

In her quiet and patient attempt to capture experiences through the language of photography, Fazzina gives a central role to the symbolism of light which often provides an almost sacred or religious quality. Most photographs have been taken at dusk and night in dimly lit streets or, most often, in the interior of doss houses and tents where migrants rest during the day. The effect is a sense of vulnerability outdoors and a sense of expectant stillness inside. As the light steals in through the makeshift rooms with walls made of pieces of wood, cupboards, or torn fabric, so the outside world is revealed only through the stories told within. It filters through as something one imagines but never sees, yet revealed potently from the person within the walls.

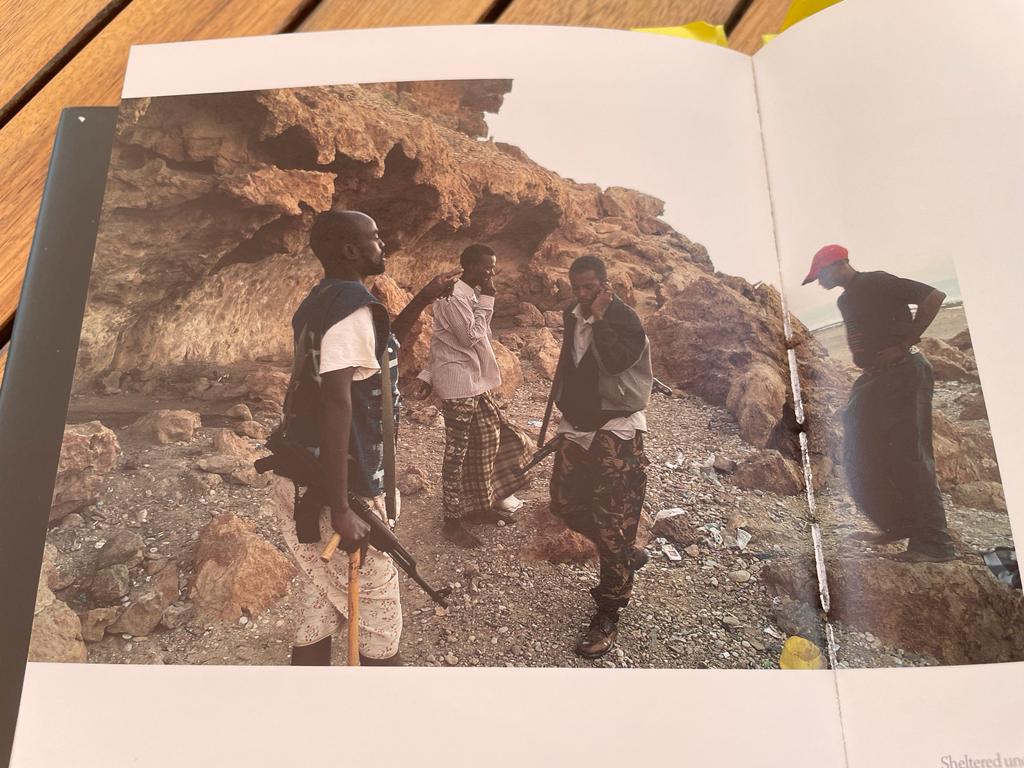

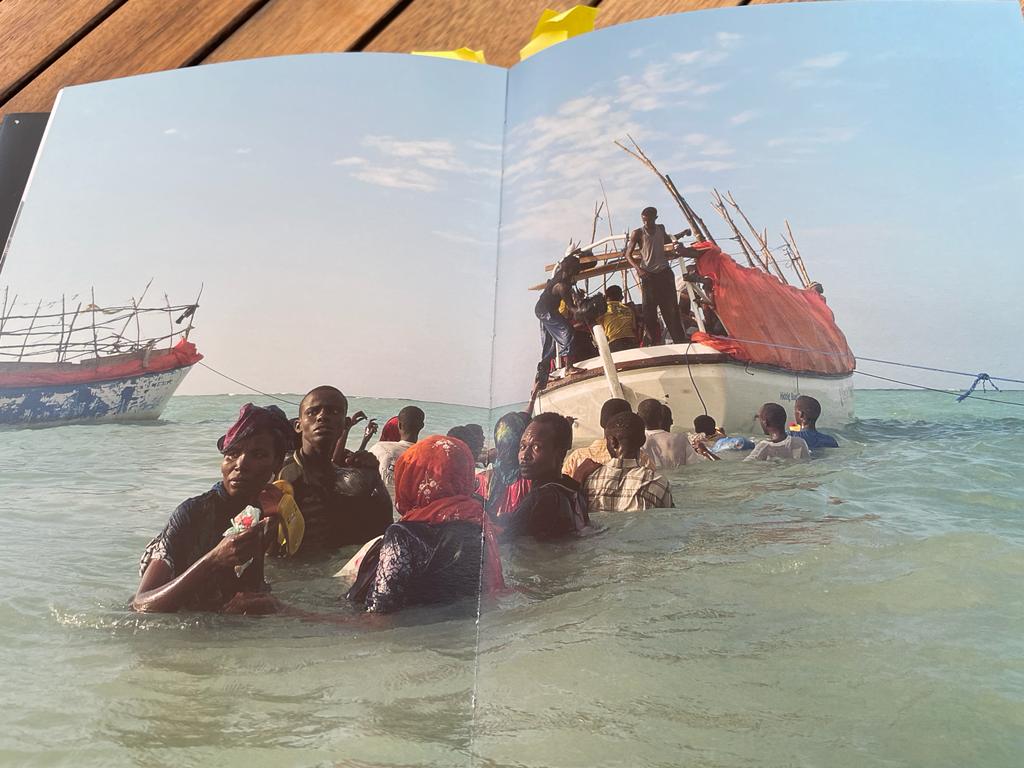

This outside world of blinding tropical light abruptly breaks into the visual narrative when the tahrib are taken in trucks to the beach from where they will cross the Gulf of Aden. Armed militia, usually young men holding Kalashnikovs and high on hashish and qat, will separate them into groups, each one to board a different vessel.

A photograph shows a group of people boarding a small boat in a turquoise sea, anxiously looking back to make eye contact with friends or relatives who will travel in other boats. Once in the boat they are tied down to prevent the vessel from capsizing. In the following page we learn that only eleven of the hundred and twenty eight people who travelled in that same boat reached Yemen alive.

Simone Weil wrote that ‘There are only two services which images can offer the afflicted. One is to find the story which expresses the truth of their affliction. The second is to find the words which can give resonance, through the crust of external circumstances, to the cry which is always inaudible: “Why I am being hurt?’’’ Perhaps it is the second service that Fazzina seems to provide through her work, using photos to tactfully express the emotions of her subjects, particularly during moments of waiting.

The indoor scenes of waiting are particularly evocative. In looking at Fazzina’s photos one wonders what sounds would be filtering through the frail walls—perhaps long silences broken momentarily by the quiet conversation between two people passing by, the fading voices of children in the distance or the flapping of a piece of cloth in the afternoon breeze. Perhaps even the call of a passing bird.